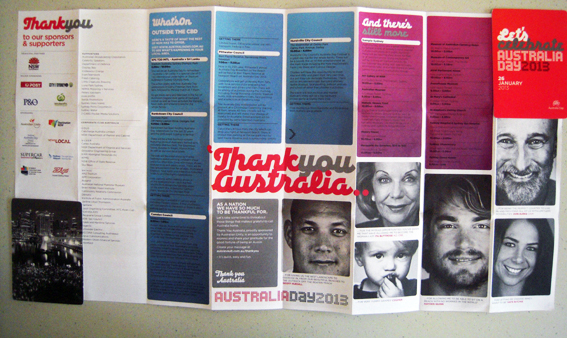

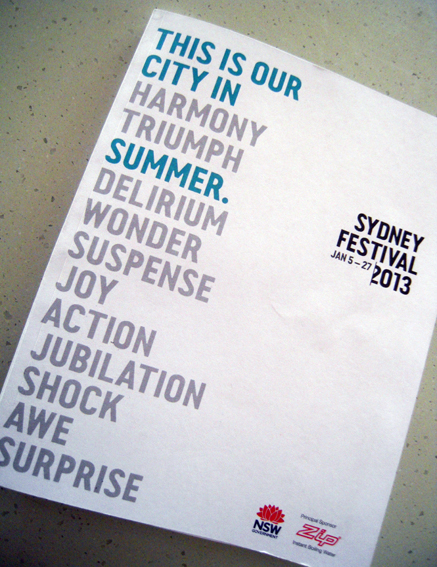

It’s Australia Day tomorrow so let’s celebrate with an unusual example of paper folding. This fold-out guide to Australia Day in Sydney 2013 was a freebie I picked up on the street. It measures only 11x8cm, including board cover, in its folded state but opens out to a double-sided 48 panel sheet. I’m not sure what the sheet size is – it’s an elongated A3 – an A3 plus two-thirds A4 stuck on the end. My guess is this sheet size is used to fit the machinery that makes it.

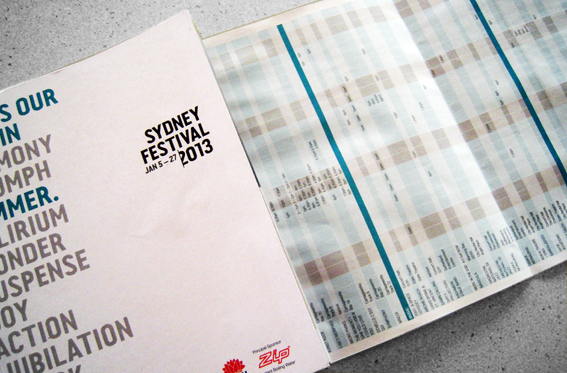

Anyway, the size is not so important as the fact that it all folds down into a neat little pocket-size item sandwiched between two celloglazed boards. People who love folding (yes, there are such people) will tell you that it is the fold that maketh the product; without a fold, all you have is a piece of paper. A fold is what creates a brochure, a newspaper, a book. This particular folded item even has its own name; it’s called a Z-Card, its branding backed up by copyright claims, trademarks and patents pending. According to its website, the Z-Card was invented in the UK 20 years ago and has now sold more than 1.5 billion items worldwide.

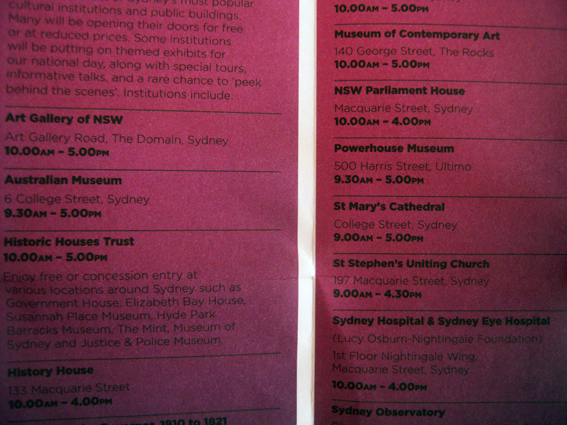

I like the compact nature of the Z-Card and the fact that so much information is included in such a small format. I love fold-outs; there’s something childishly exciting in seeing a small piece of paper expand ever bigger. Give me a map over a GPS any day. I realise the same information is also contained in a free app downloadable to any smart phone or tablet. It’s just that those words depress me slightly; folded paper makes me go ‘ooh’. And I reckon that duffers like me can find the info they need with a fold-out guide faster than it takes you to tap in your password. But that’s just me.

On the other hand, there are things I don’t like about this guide. Black type on dark red or purple is too much for my geriatric eyes. Maybe it looks good on screen, but in print, in tiny sans serif, well… it could be a bit more forgiving. Miscalculations like this don’t help the usability, which is what it is all about. Also the content is a bit light-on; about a third of it is taken up with acknowledgements of the sponsors and photos of celebs telling us why they like Australia. It’s like breakfast TV in print.

And, you know, there’s something just weird about opening it up and seeing Don Burke’s face in close-up beaming out at you. OK, so it’s as Australian as all get-out but perhaps it should carry a warning to avoid scaring small children and those of a nervous disposition. Happy Australia Day.