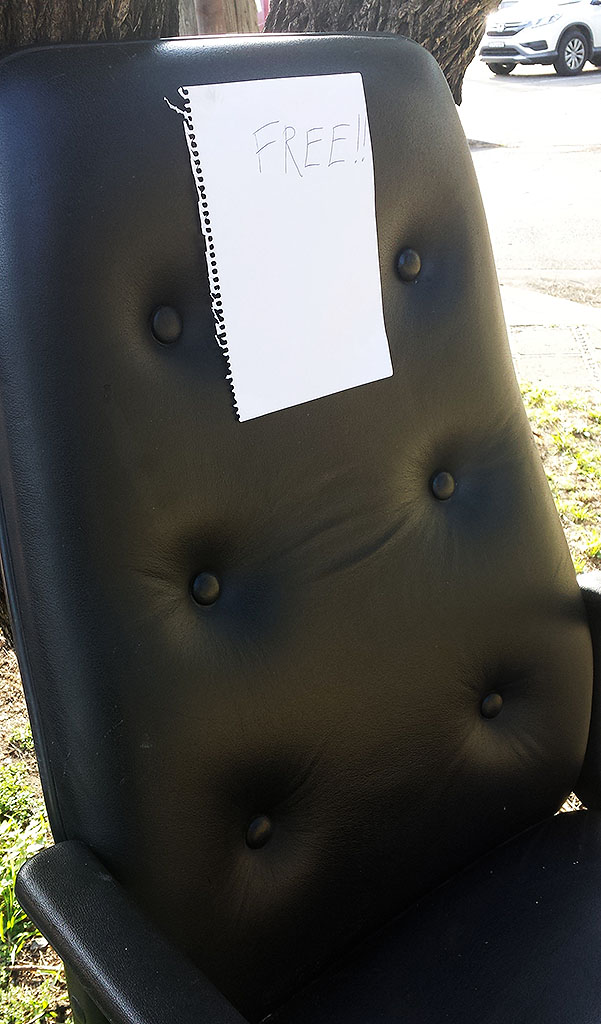

Ah yes, but are you really? Are any of us truly free?

And now, having made that obviously weak and unoriginal joke, I butt up against the ossified limits of my intelligence, a fact of which I am reminded repeatedly every day ad nauseam.

This is, after all, a rather commonplace example of misreading, something which anybody schooled in the culture of ‘Dad jokes’ will recognise instantly: corny, painful, a deliberate misrecognition of the world in order to amuse/annoy, a peculiarly persistent irritant in the daily lives of so many put-upon families.

And yet, misreading, for my mind, has long been a habitual and necessary tactic in daily life, a constant reminder that there is no such thing as a ‘natural’ or ‘obvious’ reading of a text. Reading ‘wrong’ is a critical function that goes against the grain of accepted meaning.

This is Terry Eagleton in Literary Theory: An Introduction (Basil Blackwell, 1983) arguing against the notion that ‘making strange’ is a particular characteristic of literary language:

Consider a prosaic, quite unambiguous statement like the one sometimes seen in the London underground system: ‘Dogs must be carried on the escalator.’ This is not perhaps quite as unambiguous as it seems at first sight: does it mean that you must carry a dog on the escalator? Are you likely to be banned from the escalator unless you can find some stray mongrel to clutch in your arms on the way up? Many apparently straightforward notices contain such ambiguities: ‘Refuse to be put in this basket,’ for instance, or the British road-sign ‘Way Out’ as read by a Californian.

Eagleton’s point is that all language can be ‘made strange’ if it is read in a certain way – such an appreciation is not inherent to certain types of ‘literary’ language but rather a product of how the language functions and is used. Misreading alerts us to the manner in which all kinds of messages, signals, beliefs, ideology etc are normalised because we are conditioned to read them in established ways.

It is another sad fact that in the 30-odd years since I first read the above passage, I have lost count of the number of times when, travelling on the London underground, I have been unable to resist the urge to repeat the very same observation.

As this chair will soon discover, even when ‘free’ we remain prisoners of our own paltry intellects.

Find more dead office chairs here.