Having notched up a century of dead televisions, it seems appropriate to mark this historic milestone by further considering the meaning of laneway life – and death.

The dead television was one of the first dead things to be recorded, just over three years ago now. It took about two years for the first 50 televisions to be accumulated but the second 50 has taken only a year. Undoubtedly this is mainly due to the end of analogue transmissions which rendered most of these sets useless without a digital receiver.

For a few weeks following the analogue switch-off, the carnage was unrelenting; dead sets were popping up everywhere like politicians on polling day. After a while it settled down again and now the dead television has become noteworthy for its relative rarity. They still appear, huge and lonely like fallen bull elephants, but less often. It may well be that in time they will disappear altogether.

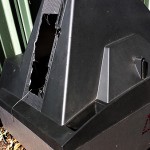

The dead television has always been easy prey for scavengers; any set left out in the open will gradually be dismembered and decomposed. Recently, however, there have been a couple of instances in which the set has had a hole punched in its side – like this one above but also this one and this – and something extracted. It is a curious phenomenon, as if it has been gutted, the choice cuts harvested, and the rest of the carcass left to rot.

The ecology of laneway recycling – the stealthy, solitary activity, not the organised pick-up – is a intriguing subject, rarely studied and yet remarkable for its ceaseless industry and pervasiveness. Every day, thousands of items are picked over and assessed, dismantled and carted off, in stages or holus bolus. In many cases, it can be hard to discern why an item has been taken apart in a particular way – as with these televisions – so that the gleaning often appears both random and yet peculiarly specific.

The result is that, in death, these mass-produced items acquire a distinctiveness that was never envisioned during their progress from conception to manufacture – homogeneity being the ultimate goal. Unlike us, whose lives are all different but for whom death renders us equal, each dead thing only achieves real individuality when its useful life has come to an end.